From the Mountains to the Sea and Everything in Between: A Journey with Oregon’s State Wildlife Veterinarian

By Amanda Bielecki, DVM ‘25

On the first day of my six-week externship with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), I shook hands with Dr. Julia Burco, a state wildlife veterinarian, and I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude and fulfillment.

Seven years earlier, while attending an undergraduate pre-veterinary club talk by Dr. Elizabeth Bunting, a Cornell wildlife veterinarian who worked with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation to co-develop a statewide wildlife health program, I experienced a pivotal moment that shaped my career path. Listening to her discuss diseases such as white-nose syndrome in bats and chronic wasting disease in white-tailed deer sparked my determination to one day serve in a similar role.

I had a full-circle moment, seven years later, as I was working alongside another remarkable leader in the wildlife disease field, assessing some of the very same issues that had first inspired me. While training with Dr. Burco during my ODFW Wildlife and Fish Health Veterinary Externship, my fascination for wildlife health flourished as I learned firsthand how veterinarians contribute to conservation and population management.

A Day in the Life of a State Wildlife Veterinarian

No two days were ever the same during my time with ODFW. While most mornings began in the office answering calls from the state’s Wildlife Health Hotline or organizing data from the California bighorn sheep captures, the day could quickly turn in an entirely new direction. I quickly learned there is never a dull moment as a state veterinarian, as you can never predict how a day will unfold.

Although less thrilling, the desk work provided valuable insights. Listening to voicemails from the public reporting injured or diseased animals and revising ODFW’s online resources on avian influenza taught me the importance of clear communication in promoting responsible human-wildlife interactions. Being a figure who can address disease-related fears and provide accurate, science-based information is a powerful aspect of the job.

Fieldwork and Collaboration: Lessons from the Wild

Some of my favorite experiences occurred in the field with the biologists. Helping to set up and collect camera traps for wolves and white-tailed deer to monitor populations throughout the Willamette National Forest stands out as a pivotal moment during my Oregon adventures. As a wildlife veterinarian, your team is only as strong as the collaboration between you and the biologists working alongside you.

Each team member approaches problems through different lenses, creating a richer and more comprehensive understanding of wildlife populations. Spending long days in the field reinforced the importance of these partnerships and the rewarding camaraderie that can develop when you share the same mission. Plus, what fun it was to join long drives with wonderful people!

Another field project I assisted with was Oregon’s Hunt by Reservation Program, which helps minimize wild turkey damage near metropolitan and agricultural areas following the species’ introduction to Oregon in the 1960s. Not only was I able to practice my avian blood draws and proper restraint techniques, but it also gave me a deeper appreciation for a veterinarian’s role in ensuring that wildlife populations remain both healthy and balanced.

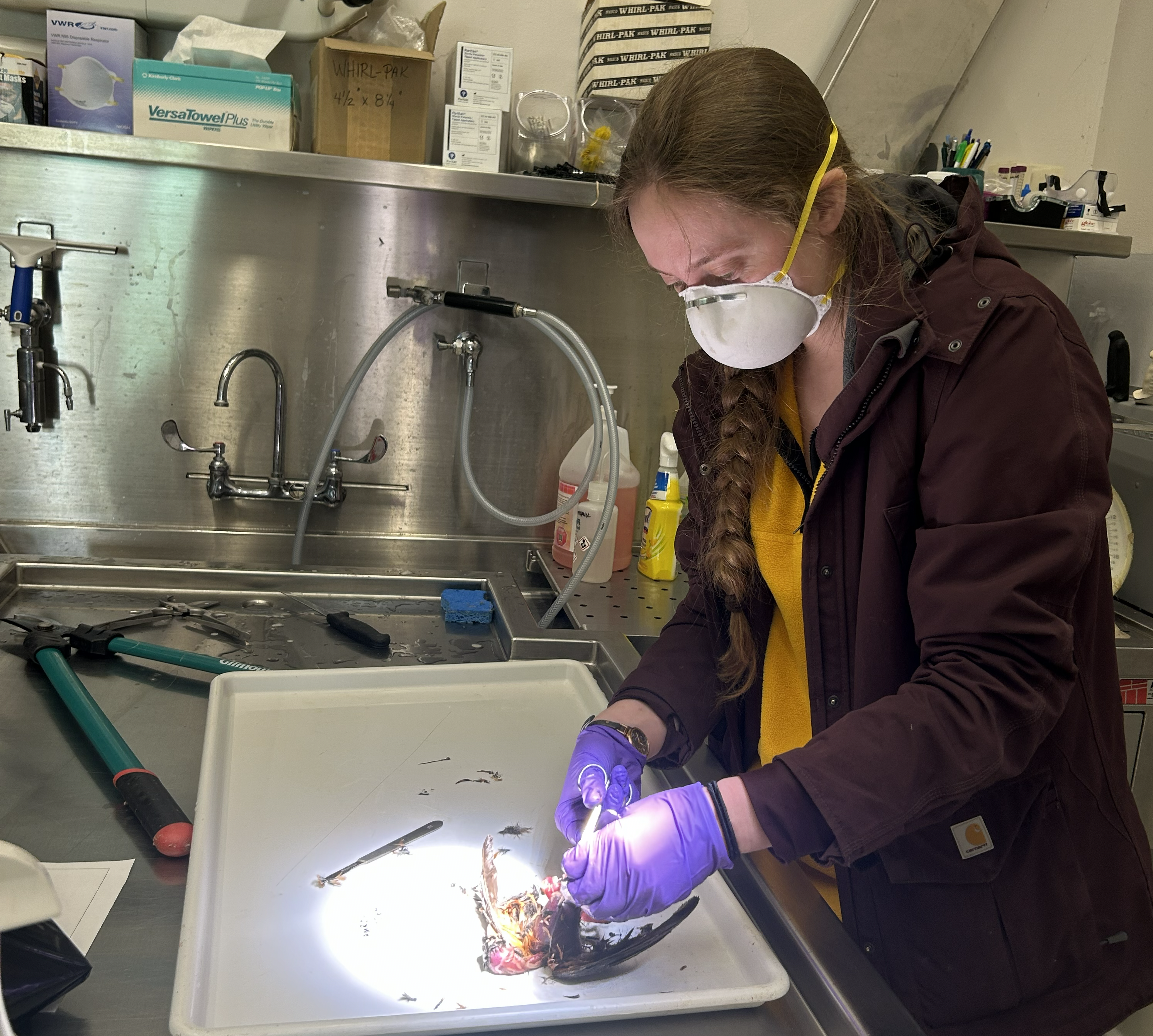

Necropsies, Disease Surveillance, and New Discoveries

When not assisting in the field, there were always wildlife necropsies to complete. On the necropsy floor, I observed diseases I had never encountered during vet school in New York, such as a bighorn sheep’s sinus tumor, elk hoof disease, and deer hair-loss syndrome. I also assisted the biologists with preparing ovary samples from bears and foxes so we could evaluate reproductive health by counting the number of corpora lutea (groups of cells that form after ovulation). I also collected kidney fat indices from deer and elk to assess overall population conditions. Each case presented an opportunity to expand my understanding of regional disease ecology in the Pacific Northwest.

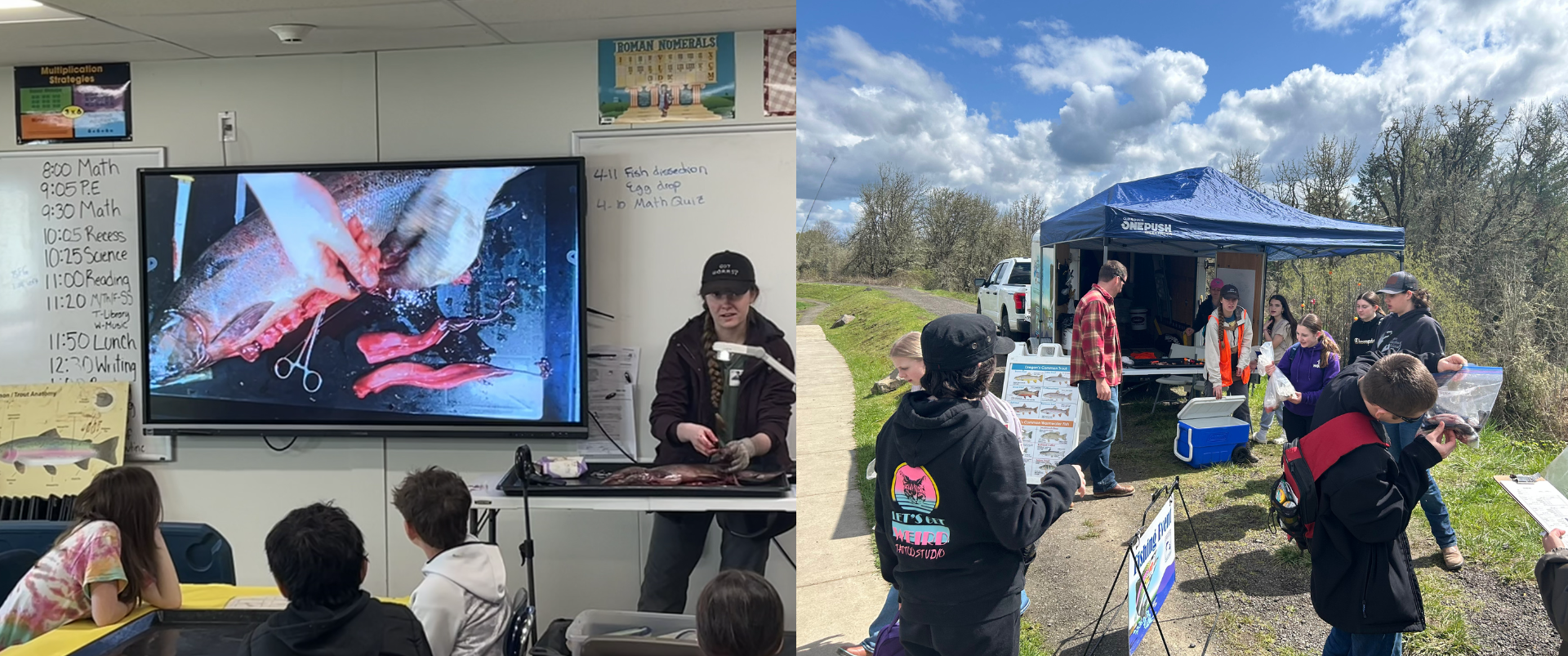

Connecting with Communities and Inspiring Future Scientists

To create an even more well-rounded experience, my interests in aquatic animal health were integrated into the externship. I joined ODFW’s fish biologists for public outreach programs that introduced middle school students to Oregon’s aquatic ecosystems. One of the most rewarding experiences during my time in Oregon was teaching students about fishing regulations, proper fishing techniques, and fish anatomy through hands-on dissections. Watching their curiosity grow reminded me of my own first spark of inspiration, and I hope the experience planted a similar seed for them.

Unexpected Adventures and Lasting Lessons

When reflecting on the weeks that could not have been any more unpredictable, I cannot forget my days spent at the Oregon Wildlife Safari. The wide range of projects kept me constantly learning, and emphasized the versatility required of wildlife veterinarians.

At the Oregon Wildlife Safari, I helped the safari team with tuberculosis testing on fallow deer and participated in darting practice. From retrieving a mallard duck and all its ducklings from a confined elementary school quad for release to performing field necropsies on elk, each day brought new challenges and rewards. I grew to admire how ODFW balanced fieldwork, disease response, and outreach, with Dr. Burco exemplifying the adaptability, leadership, and composure necessary for the job.

Looking Ahead

My main takeaway from the externship was that a state wildlife veterinarian’s life is defined by flexibility and dedication. Some days are spent at a desk juggling data sheets and calls, while others are filled with fieldwork and public engagement. The constant variety and purpose-driven nature of the job have me hooked. Each moment spent in the field, the lab, or the classroom left me inspired to continue contributing to wildlife health and conservation.

This externship experience was a highlight of my veterinary training, and I am deeply grateful to Dr. Burco for her mentorship and to the many ODFW biologists who welcomed me so warmly. Their guidance reaffirmed my goal of one day serving as a state wildlife veterinarian. I’d also like to thank Jake Holshuh '67, DVM '69, who generously sponsored this experience through the Student Support Fund.

Amanda Bielecki, DVM ’25, recently graduated from the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. She received her Bachelor of Science from the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry in 2020, majoring in biotechnology.

Following veterinary school, she moved to Alaska, where she is sharpening her clinical skills in small animal general practice and volunteering with local wildlife veterinarians. She hopes to one day return to academia to pursue a PhD focused on free-ranging wildlife management and population health-based medicine.

Photos provided by Amanda Bielecki.

Please consider giving to the Cornell Yang Center for Wildlife Health Student Support Fund to help provide more hands-on experiential learning opportunities for students passionate about wildlife health and conservation.