The Power of Policy and Gorbachev’s Ashtray

The fate of our wildlife lies at the hands of our policy makers – an obvious statement perhaps, but sometimes these forces work in unexpected ways.

Here in Tajikistan, on a beautiful day in Dushanbe, the sun filters down through an arbor hanging thick with grapes, flashing a glare across my computer screen. I am in the midst of a welcome few days of respite, snatching time to write up my research on health and it’s impact on Russia’s Amur tigers. I’m a slow writer, but gradually my manuscript begins to take shape – the culmination of seven years of work. My story traces 25 years of tiger history, using telltale antibodies in the blood of captured tigers to explain their changing fortunes and their exposure to the often lethal canine distemper virus. A key riddle is this…

Our detection of infections in a bear and a leopard in the early 1990s confirm that distemper has a long history in Russia’s Far East. Yet despite this, tigers showed no sign of exposure until the 2000s, after which the virus has become an important threat with over a third of their population now showing signs of exposure, and deaths recorded periodically since. The question is why didn’t tiger infections happen earlier….?

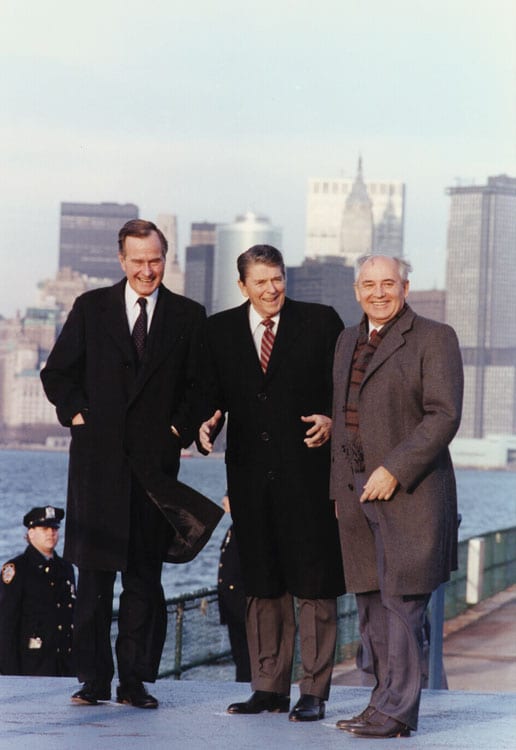

Pausing to mull on the wording of another sentence, my eyes are drawn to the cold metallic stare of a bronze ashtray on my table, fashioned in the shape of an Arabian horse’s head. Far from a mere kitsch trinket, this equine bust represents a little nugget of history. I’d been told that years earlier this modest artifact had housed the butts of none other than Russian Presidents Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin! …Considering that my host is the nephew of Tajikistan’s first premier this is quite believable. An old faded photograph shows him as a three-year old at a picnic with the architect of glasnost, during which he is reputed to have likened the Soviet leader’s bald pate to the hairless dome of his pet tortoise!

In many ways the story of my tigers and the illustrious history of this truncated horse are intertwined, for both tell of the political winds of change and the fate of the Soviet Union….

Despite its name, canine distemper virus has more cosmopolitan tastes than man’s best friend and I now know that infection of wildlife is far more important than of dogs for transmission to tigers in the Russian Far East. Among the affected species the marten-like sable is king, for these feisty and abundant small carnivores act as a reservoir of infection driving the epidemiology of the virus in wild Russian ecosystems.

Economics may lie at the heart of the tiger’s distemper story, which is driven by the unlucky sable’s one valuable resource: its luxuriant fur pelt. Viruses like distemper need a steady supply of naïve animals to infect. An infected young sable might die, but survivors become immune for life. In heavily hunted populations fewer sable survive to old age, reducing numbers of immune adults (i.e. decreasing the herd immunity), and increasing the likelihood that distemper will encounter a naïve youngster. Although difficult to prove, my research suggests that hunting may be the catalyst that has allowed distemper to flourish in the tiger’s forest. Let me explain…

Returning to history, in the late days of the Soviet Union, fur trappers plied the forest, harvesting up to 20% of the local sable population each year. Then in the dark economic days following the Soviet collapse, as Gorbachev gave way to Yeltsin, the demand for luxurious sable fur crashed, and hunting declined as trappers looked elsewhere to make their living. The respite from hunting was a boon for sable but brought hard times for distemper as immunity increased across the aging sable population, robbing the virus of naïve hosts. In these conditions, the exposure of tigers also slowed, as revealed by our blood samples from the 1990s. But the effect was short-lived.

By the close of the decade a new more outward looking Russian state and burgeoning international trade opened new markets for fur, leading to a return to hunting. By 2000 fur trapping had reached pre-Glasnost levels and has intensified since, with as many as 40 or 50% of sable hunted each year in 2013 and 2014.

With hunting at these scales few sable survive into adulthood, and the younger naïve population is for distemper what a tinder-dry forest is for wildfire. As distemper flares-up, spread to tigers is inevitable, and although infrequent, can be enough to threaten their rare and fragile populations.

Back at my computer in Dushanbe and grappling with my writer’s block I look across at Gorbachev’s horsehead gazing back from his perspective of history. Time moves on and the changes he’s seen bring hope. While today he sees a world full of challenges for tigers, he also sees a society becoming more urbanized and abandoning their rural ways. Looking ahead, perhaps he sees a future with society reshaped by the forces of policy and economics, and a time when the interplay of hunting and disease becomes kinder on the lives of the sable and the tiger.

Martin Gilbert is actively fundraising to support field studies to address gaps in our understanding of wild carnivore ecology and disease threats, which are critical to effective conservation.

For further information: