How a Childhood Love of Lemurs Led Me to the Weird and Wonderful World of Eupleridae in Madagascar

By Shayna Orens, Cornell DVM ‘27

As a young child, an eager zoo camper, and later a teen volunteer at the Maryland Zoo in my hometown of Baltimore, I was always drawn to the lemurs in the zoo’s collection: I was hooked on the unique locomotion of the Coquerel's sifaka, the red ruffed lemurs’ striking eyes, and the ring-tailed lemurs’ incredible tails. Lemurs are our most distant living primate relatives; we shared a common ancestor over 60 million years ago. As our distant cousins, they seem so like us and so unlike us at the same time. I wanted to know everything about them. I wanted to see them in their habitats across the island of Madagascar.

The Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine’s Expanding Horizons Program gave me the incredible opportunity to spend the summer between my first and second years of veterinary school in Madagascar. But there’s a plot twist: I didn’t spend my entire summer working with lemurs!

Under the guidance of veterinarian and epidemiologist Dr. Fidisoa “Fidy” Rasambainarivo, I discovered the weird and wonderful world of Eupleridae, one of the most endangered families of carnivores in the world. The Eupleridae family is endemic to Madagascar and includes a peculiar cast of characters. These include Galidia elegans, commonly known as the ring-tailed vontsira (also called the ring-tailed mongoose even though it is not actually a mongoose), and Cryptoprocta ferox, commonly known as the fosa (pronounced FOO-sa).

If you’ve watched the “Madagascar” movies, you may remember the fosas as the bad guys that eat lemurs. While lemurs are admittedly part of fosas’ diets, there’s much more to these creatures, beginning with their unique anatomy. Fosas are the only non-felid to have semi-retractable claws, which help them grip onto tree trunks. They are the only terrestrial mammal that can switch between a digitigrade gait (how dogs and cats walk) in the trees and a plantigrade gait (how people walk) on the ground. Their tail is nearly as long as the rest of their body, providing crucial balance in the trees.

Understanding more about fosas, like their health status and movement patterns, is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies for this creature that, for all its weirdness, hasn’t received the same research attention as the more well-known lemurs. As the island’s apex predator, the fosa’s fate is closely tied to that of the rest of the plants, animals, and people with whom the fosa shares its forest home. Turning our attention to the conservation and health challenges of these curious carnivores could go a long way in saving Madagascar’s many other iconic species.

One such challenge is Madagascar’s large population of domestic dogs and cats. As invasive species on the island, they carry infectious diseases, compete with native species like the fosa for access to food and other resources, and may prey directly upon native species. While Madagascar has laws prohibiting dogs and cats from protected areas, enforcement is weak, and communities may not be aware of these policies. Recognizing the potential for the spread of disease between domestic animals and wild carnivores, Dr. Fidy has spent several years monitoring wild carnivore health. An important part of this work is collaborating with communities to collect blood and fecal samples from village dogs and cats. This helps us understand which pathogens are circulating in these populations and where there may be potential for disease to spread between domestic animals, wildlife, and people.

Our main field site was in a protected lowland forest called Betampona. My journey to and from Betampona impressed upon me how many unsung heroes there are in conservation work. I have never witnessed an athletic feat like that of the porters hiking up the mountain with our equipment, barefoot. It’s the same with the drivers who navigate unpaved roads in ancient stick shift trucks, the cooks who feed the field station staff, the guides who gracefully navigate difficult forest terrain, and the guards who keep us safe at night. I will never stop thinking about how many people it took to get us to and from Betampona safely, and how many people it takes to support a large research team. They do what is often backbreaking work during the field seasons—work that benefits local village communities throughout the rest of the year. They are essential to moving conservation science forward.

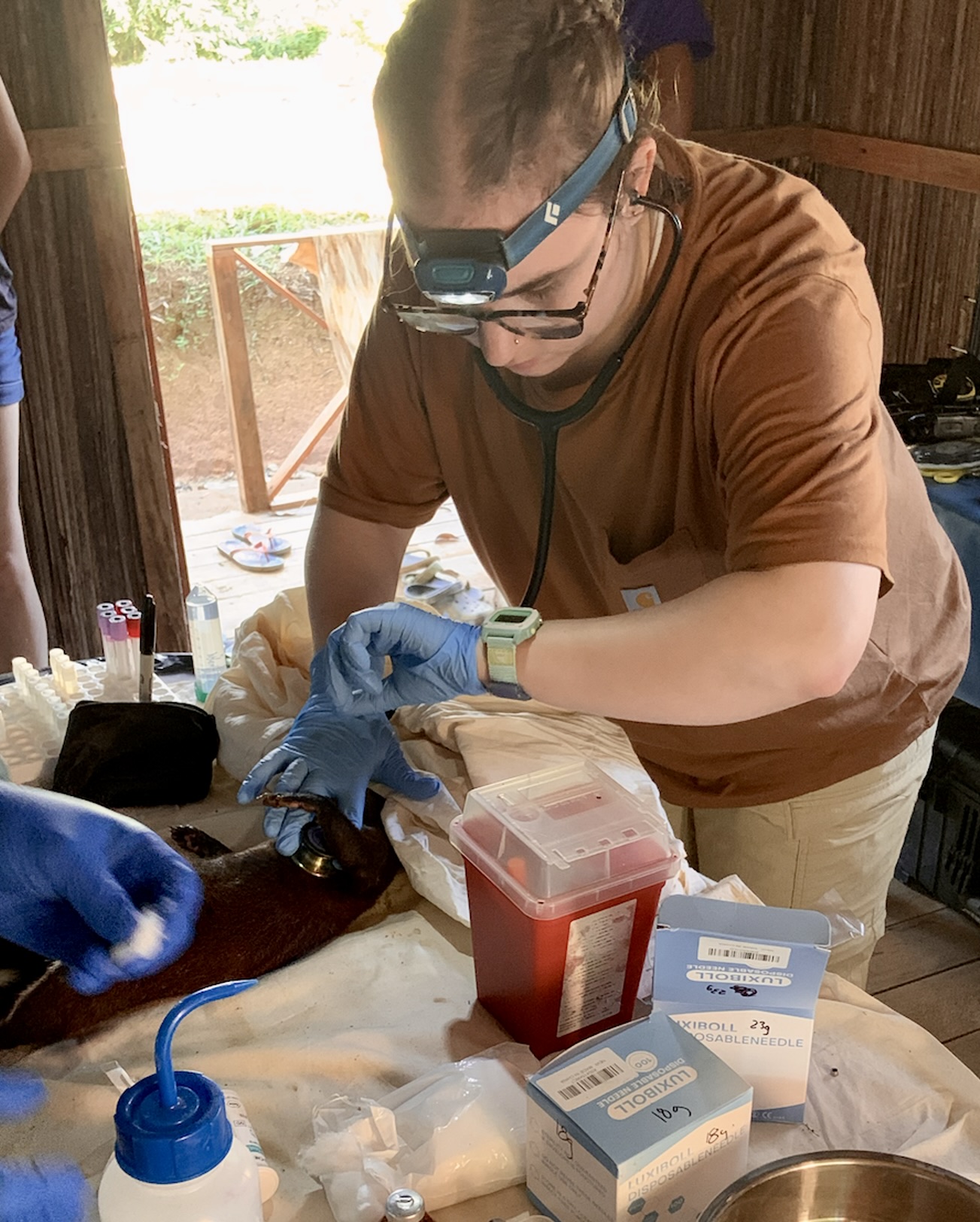

With the help of expert guides, our team captured 18 carnivores, including two fosas. Each individual was anesthetized, and a full physical examination was performed. Newly captured animals were microchipped and radio-collared so that Dr. Fidy’s research team can learn more over time about how the animals use the habitat and any potential interactions with domestic animals, including livestock, in villages. During the physical exams, the team collected blood, fecal, urine, and hair samples to take back to the lab. As part of a larger team of interns, I rotated through assisting with capture, tracking collared animals in the forest, and collecting environmental samples. I was fortunate to experience both the joys and the rigors of fieldwork and wildlife medicine. I also got to know veterinary students, graduate students, and young researchers from Madagascar who are devoting their careers to their country’s amazing wildlife.

I returned to the capital city of Antananarivo to work at Mahaliana Labs, the first biosafety level 2 laboratory in Madagascar devoted entirely to wildlife health. I prepared samples for DNA/RNA extraction and performed white blood cell counts on slides we made in the field. In my final few weeks in Madagascar, I traveled to the west, where fosas live in an entirely different dry forest ecosystem.

At the Ankoatsifaka field site in Kirindy Mitea National Park, I had the opportunity to observe the Verreaux’s sifaka (sometimes called the dancing sifaka because of their unique terrestrial locomotion), which have been studied by researchers from the University of Texas at Austin for more than 20 years. In Kirindy Mitea, I assisted Olivier, a vet student from the University of Antananarivo, with capture, euthanasia, and tissue collection from invasive rodents. Unfortunately, invasive rodent species also pose a disease threat to Madagascar’s wildlife as well as its people. Rodent tissue samples will help us better understand the diseases that invasive rodents carry. By assisting with this project, I was able to use my anatomy knowledge to help guide undergraduate interns through rodent dissection and tissue collection.

My last two days in the country were unexpectedly two of the most meaningful and thought-provoking. A vet student I befriended in the lab, Miti, invited me to visit a charity where she volunteers called Animal Voice Madagascar. The organization runs a shelter for injured and abused street dogs, providing both a home and life-saving veterinary care. While the hope is that some of the resident dogs will be adopted, most will live their entire lives at the shelter.

Miti and I neutered a newly rescued dog named Bolo, who was undergoing a forelimb amputation. He had extensive injuries, and the amputation would save his life, but it was a challenging procedure to perform outside of a hospital. Madagascar’s human health system is already under immense pressure, leaving few material resources for veterinarians; the fact that dogs are seen by many as a nuisance adds to the challenge. Though I love dogs and cats, I also know they can be a real problem for people, and for the wildlife we’re working hard to save. It is my responsibility to acknowledge that domestic animals are a major challenge in public health and conservation. And yet, I wouldn’t be upholding the professional oath I will soon take if I didn’t also acknowledge that these animals, such as Bolo, still deserve our attention and humane care.

Madagascar is a fascinating country. It’s home to some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth, which are among the last remaining strongholds for critically endangered lemurs as well as fosas, vontsiras, and so many other unique creatures. It was a privilege to have the chance to see some of these places. But for many people living in these biodiversity hotspots, the combined challenges of extreme poverty, food insecurity, and lack of access to health care means that immediate needs tend to supersede the protection of ecosystems and wildlife.

Conservation, not just in Madagascar but throughout the world, can only be successful if it also makes life better for people. And I believe that it can. Veterinarians can serve a crucial role in helping people understand how the work we do for animals, whether in wildlife conservation or through vaccination and sterilization of street dogs, benefits people too. The One Health concept, the recognition that the health of people, animals, and the environment are inextricably linked, became very real for me this summer. I’m excited to continue dedicating my veterinary career to putting this idea into practice.

Shayna Orens, Class of 2027, is a DVM student at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. She holds a bachelor’s degree in political science and sustainable development from Columbia University and a master’s degree in public policy from the University of Southern California. Shayna aspires to be a leader in the field of One Health. She seeks to bridge the social sciences with veterinary medicine by working at the intersection of clinical medicine, epidemiology, conservation, and public health. Shayna’s clinical interests are currently in zoo and wildlife medicine, neurology, and behavior.

Photos provided by Shayna Orens.