My Rhinoceros Teacher

5:30 AM

As dawn yawns and stretches over the African savanna, a line of cars waits impatiently at the wooden gate of Crocodile Bridge Rest Camp. I join the tail end in my tiny white rental car, exhausted from an annual weeklong scientific conference (the Savanna Science Network Meeting in Kruger National Park), but determined to make the most of my trip to South Africa.

This year, I am on a mission. I'm going to see a rhino.

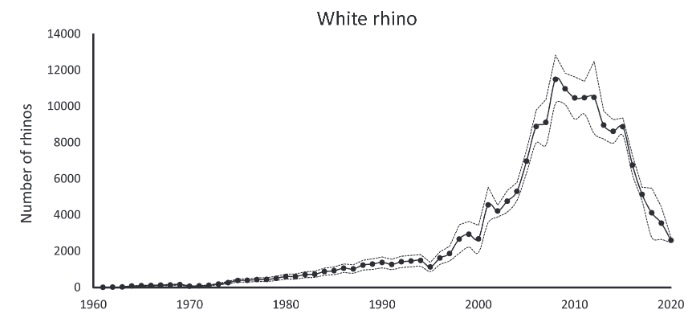

South Africa's flagship protected area, Kruger National Park, has a massive problem: the white and black rhino populations have taken a nosedive since the early 2010s and are struggling to recover.

It's not disease, predation, or war that has caused 51% and 75% declines in black and white rhinos, respectively, from 2011 to 2020. It's poaching. The increased demand for rhino horn from Asian markets (particularly in Vietnam) has driven a huge spike in the practice, in which poachers illegally shoot rhinos, cut off their horns, and leave the corpses behind.

Unfortunately, this practice has become all too common. One of the presenters at this year’s Savanna Science conference showed us a photo of a mother rhino and her calf caught on a camera trap. She was excited to share her photos with game guards, but they told her that the same duo was found dead, horns stolen, only a few days later.

Rhinos were, until recently, a conservation success story in Kruger National Park. Both species were reintroduced to the park in the 1960s and 1970s, and slowly increased to sustainable levels. But after demand for black-market rhino horn rose in 2008, population declines were exacerbated by a severe drought in 2016. White rhino populations, in particular, struggled to recover from the two-pronged hit to their numbers.

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic put a pause on poaching, but as lockdown restrictions lifted, poaching levels rose.

While much of law enforcement focuses on the supply side in southern Africa, demand for rhino horn drives the market. Historically, Chinese and Vietnamese medicinal traditions have used powdered rhino horn to treat fever and arthritis. Most of today’s demand, however, comes from the wealthy as a status symbol, and from patients desperate to treat their cancer, an application absent from traditional pharmacopeia. Evidence for medicinal claims remains scant, with practitioners often citing unsubstantiated urban myths and miraculous cures. Despite this and the prevalence of fake horns on the market, demand for rhino horn continues to soar.

As the gates swing open and car engines start up, I wonder if today I'll see my first rhino (ever) in Kruger. Then, I think to myself—could it also be my last?

12:00 PM

Hours have passed, and the sun is now high overhead on a blistering day. I'm driving along in the park despite the heat, fatigued but determined.

Then, out of the corner of my eye, so fast I almost miss it: a blur of gray in a pool of mud.

Surely, it's just a rock—one of the hundreds of huge granite boulders that dot the southern Kruger landscape. Or perhaps it is a mud-splattered water buffalo, or a resting elephant, or a hippo that has lost its way?

And yet. I squeal to a stop, then reverse my diminutive car past the shrubby sicklebush blocking my view. There, a gray form lies in the mud, still as stone. A rhino.

A lonesome ear flicks up as a red-billed oxpecker hunts for ticks within. Slowly, an eye opens, and I wonder what the rhino sees when he looks at me.

I take a closer look at this rhino, calmly lazing in a muddy pool. With animals, as with many things in life, form follows function. The afternoon sun illuminates his tough gray hide. While this rhino’s powerful legs, capped in three-toed feet, can carry his bulk vast distances at impressive speeds, here they splay in the mud as he lounges peacefully.

Southern white rhinos (Ceratotherium simum) like this one are built for grazing. His wide, flat mouth is perfect for eating short grasses. His cousin, the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), has pointed, prehensile lips, just the tool for plucking leaves from bushes as he browses.

When ecologists talk about biodiversity loss, we don't just mean the loss of individual animals. These creatures are critical members of an ecosystem and play important roles in maintaining the savanna landscape. White rhinos are excellent engineers of grazing lawns, maintaining the balance of trees and grasses on a healthy savanna while supporting many other grazing species. They transport nutrients and seeds across vast distances through their gut and churn up the landscape as they wallow in the mud.

And their horns... well, this rhino doesn't have its famous horns. That's because he's been "dehorned," a practice instituted in Kruger to protect rhinoceros from poaching.

For the dehorning process, like a scene straight from an action movie, rhinos are located via helicopter and darted from midair by a trained veterinarian. Once the drugs take effect, a ground team swoops in to blindfold the patient and make sure it’s handling anesthesia well. Because no nail clippers are large enough to fit a rhino’s horn, the main job of horn removal comes down to the delicate application of a chainsaw. Like trimming our fingernails, dehorning is a painless process. Because the horns gradually regrow over time, the procedure needs to be repeated periodically.

While the absence of a horn can cause problems for an individual rhino, interfering with foraging and fighting, this dehorning procedure is one of the best tools park managers can implement to discourage poaching. Without their horns, rhinos are useless to poachers and are more likely to live another day.

I stay for a few minutes, still in shock that I'm only three yards away from a rhinoceros in Kruger. The rhino rolls over in the mud, disturbing the oxpecker and hundreds of flies, then settles in for a nap. I continue my safari drive and leave him to his slumber.

5:00 PM

As I make my way back to camp for the evening, I stop by the mud pool again. This time, it's empty, the rhino long gone. I stop briefly, thinking about shifting baselines and what they mean for rhinos.

In an oft-cited 1995 article, marine biologist Daniel Pauly described "a gradual accommodation of the creeping disappearance of resource species." If we believe that the way things are now is how they have always been, we lose the ability to imagine a return to previous abundance.

If we believe that the way things are now is how they have always been, we lose the ability to imagine a return to previous abundance.

Talking to other researchers at the conference, I learn that even 15 years ago, it was common to see rhinos as far north as Satara Rest Camp. Now, they are largely restricted to the far south of the park. Considering their limited distribution today, it's hard to imagine a time when seeing a rhino here was commonplace.

For better or worse, the human brain is better at adapting to these quick changes than ecosystems are. Remove a key player like the rhino, and the ecosystem may struggle without a species to fill that niche. This is why the biodiversity crisis is alarming to ecologists and conservationists, much like the climate crisis—less biodiversity means fewer species able to maintain our ecosystems as we know them.

Before my thoughts can completely spiral about the collapse of our planet's ecosystems, I'm struck by the feeling of being watched. I turn towards the sun and squint, then gasp.

There he stands, just behind my car, like he's been waiting for me. My rhinoceros friend.

I grin and pull up my camera to capture the moment. But then, I pause. I take a minute to soak in his presence—his tiny ears and massive girth, thick gray hide, and wide flat muzzle. I wonder what he has seen and experienced, and how he has survived until now.

I wish him more good luck and many mud baths to come. He turns, and I snap a picture, more to preserve the memory than anything else.

One more photo and, just like that, he's gone again, into the bush.

I'm so grateful to the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability for funding my postdoctoral work and this research trip.

Dr. Maggie Swift is a computational savanna ecologist at the Cornell K. Lisa Yang Center for Wildlife Health. She is currently a Cornell Atkinson Postdoctoral Fellow working with Dr. Steve Osofsky (Cornell) and Dr. Robin Naidoo (WWF-US) on predictive modeling to evaluate how African elephants might respond to a range of veterinary fencing scenarios near the Okavango Delta.

All photos provided by Dr. Maggie Swift. Location and time data have been removed for the safety of the rhino.