Deer Brains and Duck Botulism: A Month with Nevada’s State Wildlife Veterinarian

By Claire Glover, Cornell DVM ‘25

After reading the alumni spotlight on Nate LaHue, DVM ‘13, during my second year of veterinary school, I knew I wanted to explore wildlife work in a government agency and decided to reach out. Dr. LaHue, the state wildlife veterinarian for Nevada, is focused on free-ranging wildlife and population health, which aligns with my growing passion for One Health and conservation. Last summer, I spent several months in Uganda working with the Jane Goodall Institute on chimpanzee conservation as part of Dr. Robin Radcliffe’s Conservation with Communities course. My time in Uganda exposed me to a community of like-minded conservationists and One Health practitioners. I knew I wanted to incorporate free-ranging wildlife into my clinical year.

I had first started to focus on government wildlife agencies after attending a talk by Peregrine Wolff, DVM ‘84, whose experiences as a Nevada state wildlife veterinarian and subsequent work with the Wildlife Disease Association inspired me to pursue a career that combines individual and population medicine. In the blink of an eye, I went from cold emailing Dr. LaHue to boarding a plane bound for Reno, Nevada, to complete a four-week externship during my fourth year. I was excited to experience the diverse range of projects and responsibilities of the sole wildlife veterinarian managing a state full of a variety of wildlife, emerging diseases, and countless stakeholders.

Balancing Fieldwork and Laboratory Analysis

Every day working for the Nevada Department of Wildlife was different. Many days were spent in the office, doing the less glamorous but essential work of analyzing data on Nevada’s wildlife populations so as to be able to better protect them. I listened in on meetings about strategic plans for various species and performed a literature review to support the elk management plan’s section on current disease concerns, which included viral hemorrhagic diseases, brucellosis, and Treponema-associated foot disease. I even honed my statistics skills by analyzing capture data for mule deer and determining bluetongue disease prevalence over time.

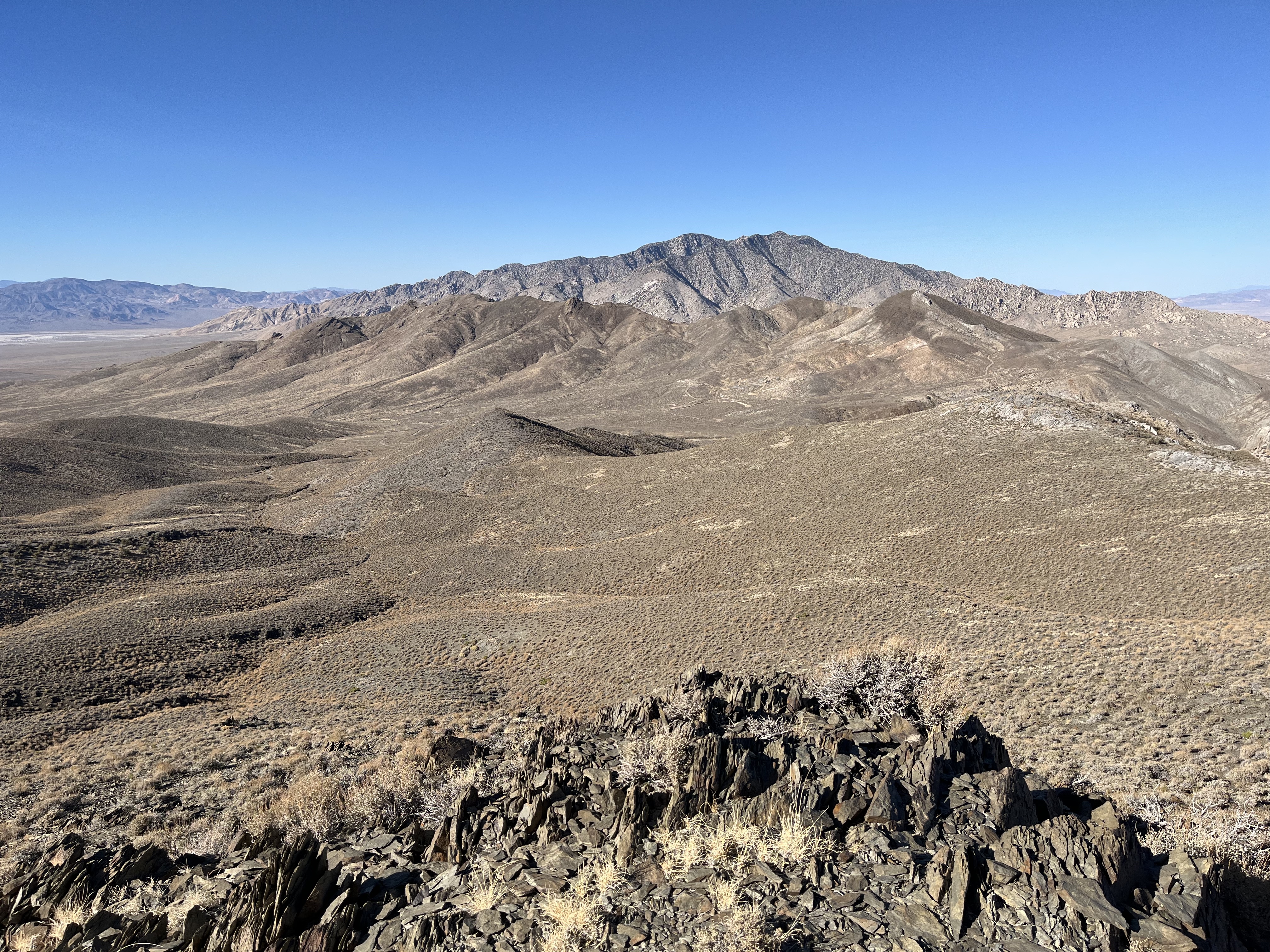

Of course, my time in the field was a highlight. I explored what was a completely new environment for me, with unique wildlife. I spent one day on a boat checking waterfowl for botulism following an apparent outbreak, and another watching a bear release in the Tahoe mountains after it had been trapped in an urban dumpster. Dr. LaHue and I camped out in the desert for several days to survey a bighorn sheep population for calf survival, which involved radio telemetry and lots of hiking. I loved seeing wildlife in their natural habitat and knowing that the behind-the-scenes work was making significant impacts on their survival.

My fieldwork was complemented by time in the necropsy lab, where I helped determine causes of mortality in wildlife sent from across the state. I necropsied spruce grouse and a bear, and tested bighorn sheep for nasal sinus tumors and Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, a type of bacteria that can cause respiratory infections. These experiences provided important real world examples of emerging disease surveillance, human-wildlife conflict, and cooperation between state agency departments, nonprofits, and the public. Dr. LaHue regularly communicated with colleagues, researchers, law enforcement officers, wildlife technicians, and other stakeholders to protect Nevada’s wildlife.

One of the primary projects during hunting season was chronic wasting disease surveillance in mule deer and elk. While Nevada hadn’t yet identified a positive case, the disease has been confirmed in California. Dr. LaHue and the Department of Wildlife established a mandatory testing area for all hunters near the California border (with brain and lymph node tissue samples being collected to better evaluate the risks of introduction of chronic wasting disease into Nevada), and a voluntary testing program statewide. I spent several weekends at testing checkpoints, educating hunters about chronic wasting disease and collecting tissue samples. I enjoyed connecting with the public and learning about hunting culture in Nevada, as well as about the pathophysiology of chronic wasting disease.

Future Directions

After my externship wrapped up, I spent a few extra days backpacking in the High Sierras before returning to the full-speed-ahead rotations waiting for me back at Cornell. It was the perfect opportunity to reflect in the wilderness, the place I feel most at ease. I am so grateful for the opportunity to build on my clinical skills and explore new avenues within wildlife medicine. To work and learn alongside people equally invested in wildlife health and the interconnectedness of animals, humans, and the environment was truly a gift. I left Nevada feeling affirmed and inspired, ready to take on the rest of my clinical rotations and set myself up for a future career in conservation.

I am so grateful to Jake Holshuh ‘67, DVM ’69, who generously sponsored my experience in Nevada and made this externship possible through the Student Support Fund. I also owe a huge thank you to Dr. Nate LaHue for mentoring me and making my dreams seem achievable, and to everyone at the Nevada Department of Wildlife for hosting me.

Claire Glover is a fourth-year veterinary student (Class of 2025) at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine with interests in free-ranging wildlife conservation and One Health. She received her Bachelor of Arts from Mount Holyoke College in 2021, majoring in chemistry and biology. She is also an avid backpacker and thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail in 2021.

All photos provided by Claire Glover.

Please consider giving to the Cornell Yang Center for Wildlife Health Student Support Fund to help provide more hands-on experiential learning opportunities for students passionate about wildlife health and conservation.