Veterinarians as Custodians of Coral Reefs

By Hery Ríos-Guzmán, Cornell DVM '24

A Brief Encounter With a Reef

We strap on our snorkel gear and jump into the blue. It only takes a few butterfly kicks to reach a citadel bustling with life. Within seconds, we are greeted by branching, massive, and laminar structures formed by hundreds of genetically identical individuals. Their shapes, accentuated by their colorful symbiotic dinoflagellates, reveal a community - an ecosystem. Countless species of fishes, crustaceans, bivalves, gastropods, and cephalopods make their houses within and around these calcareous forms. The melody produced by the reef’s inhabitants includes whispers of sharks, dolphins, and other predators. The ebb and flow of the ocean’s currents remind us that these ancient lifeforms cover less than 1% of the ocean floor, yet they sustain 25% of all marine life. These ecosystems - coral reefs - provide food, coastal protection, and economic resources to countless humans all over the world, too. Our return from the quiet admiration yields a thought: we are lucky to share the planet with these amazing creatures, amalgams of mineral, plant, animal.

Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease – A Coral Reef Pandemic

When I was an undergraduate student, I was lucky enough to complete an internship at Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium. While there, I was told by my principal investigator (PI) why I had been selected. “It made sense. Corals are animals, and veterinarians help animals.” The statement was said with little more than a shrug, but her words continue to drive my goal of becoming an aquatic veterinarian to this day.

But what would prompt a veterinarian to help corals? Do corals even get sick? Unfortunately, corals are as delicate as they are beautiful. Reefs face a myriad of challenges, including ocean acidification, rising sea temperatures, increasing meteorological disturbances, and even boat strikes. These events cause metabolic stress. And, just like students during finals, stress leads to reduced immune function, which results in disease. In other words, corals can get sick and veterinarians need to have the tools to treat them.

While there are many diseases corals can be afflicted by, there is one that currently warrants attention: Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD). This pandemic is currently sweeping through the Caribbean, affecting coral reefs from Florida to Barbados and everywhere in between. As the name suggests, the disease causes coral tissues to slough, eventually leading to a coral colony’s death.

This may sound like coral bleaching, but there are a couple of big differences. Coral bleaching is the process whereby corals expulse their photosynthetic algae, generally known as endosymbionts, from their tissues. In other words, the coral tissue (i.e. the coral itself), remains intact. Furthermore, corals can recover from bleaching, under the right circumstances. SCTLD, on the other hand, is more lethal. This disease process causes corals to completely lose their tissue, endosymbionts and all. Unfortunately, afflicted colonies never recover; once a coral is afflicted by the disease, it will die within days to weeks. To make matters worse, the disease affects 20 out of 22 species comprising the only reef in the continental US - the Florida Reef Tract. Not to be a pessimist, but we also don’t know what causes the disease, so we don’t know how to treat it!

Remember that pretty picture I attempted to paint in your mind’s eye in the first paragraph? It is my mission to ensure that my children and my children’s children are able to experience those wonders. As such, as a veterinary student (and future veterinarian), I would like to help elucidate the cause of SCTLD and aid in the development of successful treatments that may halt and eradicate it. Thanks to the Cornell Wildlife Health Center Student Support Fund, I was able to assist multiple researchers with projects that aim to do just that.

Coral Adventures - From Bayahibe to Seattle

My project had two main objectives. First, I went to the Dominican Republic to collect coral samples and transport them to Seattle, Washington. All samples were obtained prior to my arrival by an amazing organization called FUNDEMAR: the Dominican Foundation for Marine Studies. Everything from health assessments to social media management is handled by the inspiring individuals who work for this organization. I was able to see how they work tirelessly to ensure that the future of their reefs is maintained. And their efforts are paying off. The entire community around the organization was invested in the reefs that adorned their coasts, most likely a result of FUNDEMAR’s outreach.

My biggest challenge while in the Dominican Republic was bridging the gap between Dominican and American law, especially regarding the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Both countries had different rules regarding what should and shouldn’t require a CITES permit. This led to multiple phone calls, emails, and chats to ensure the correct permits were obtained, and that efficient transport methods were used. It was very nerve-racking to walk into the airport with a bag filled with coral samples not knowing if I would be able to fly with them to my next destination. Thankfully, 99% of all my samples made it to Seattle! Unfortunately, the remaining 1% were lost in transport, and will most likely never be found.

I’ll pause here to talk about some of my biggest takeaways from this courier experience. First, conservation work is technically and bureaucratically challenging (e.g. bridging national laws). Second, science is not perfect, as mistakes and uncontrolled variables (e.g. losing samples via transport) skew even the best studies. And third, none of the above should hinder progress. We must continue moving forward, despite the trials and tribulations, because many animals and people depend on our work.

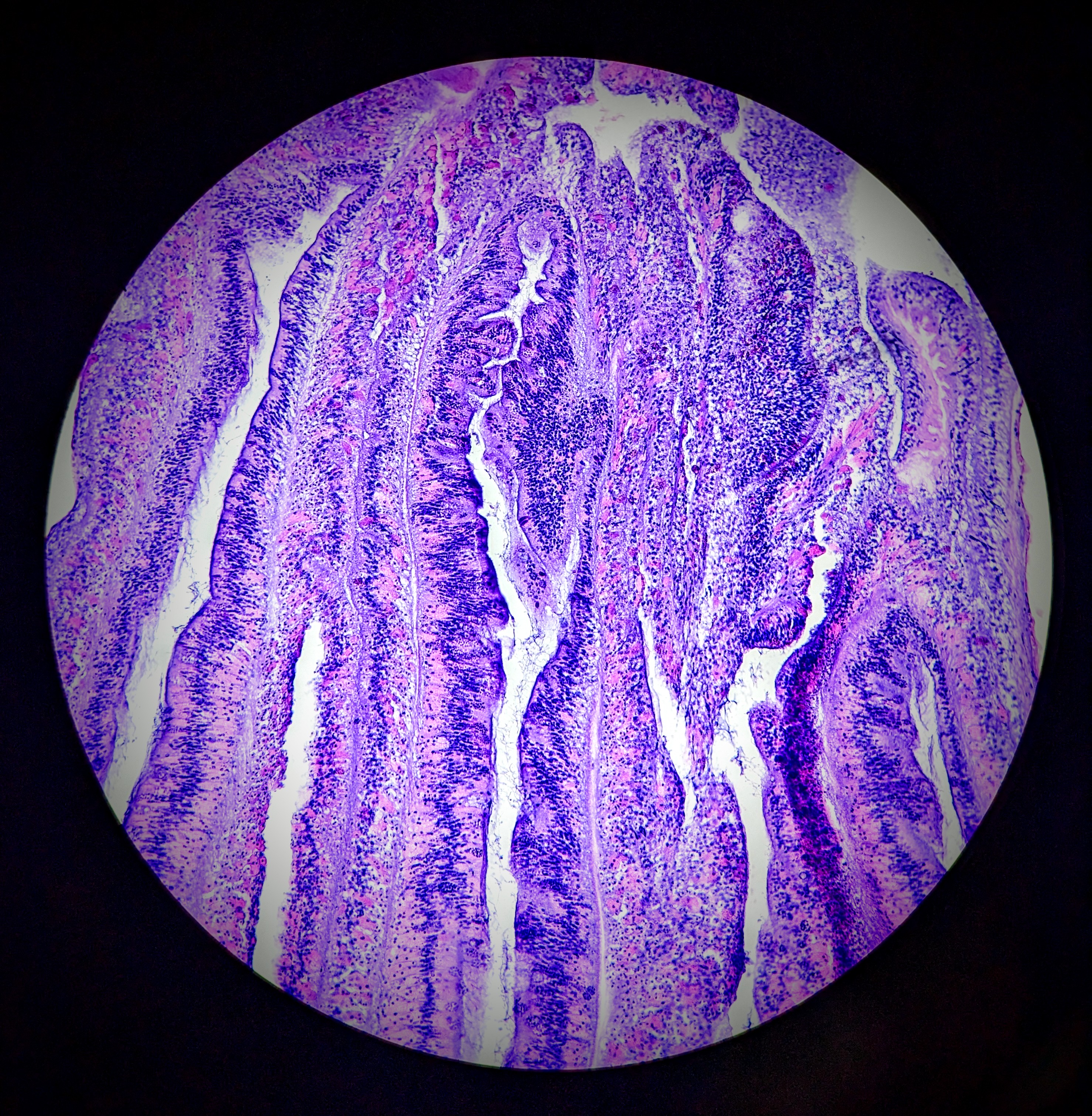

My project’s second objective was to evaluate the health and density of the coral samples’ endosymbionts (photosynthetic organisms that adorn coral tissues). However, before my assessment, I was trained in the preparation of histologic samples. This included decalcifying, trimming, paraffin-embedding, and tissue staining. I was then tasked with using a microscope to determine the status of the endosymbionts.

It was very challenging to evaluate the health of corals and their endosymbionts because coral polyps are very soft after decalcification. This results in a variety of shapes, sizes, and tissue orientations unique to each individual species. In other words, evaluating coral histologic samples is an art that requires patience and experience since no two samples will look the same. Thankfully, the amazing mentorship that I received at the United States Geological Survey – Western Fisheries Research Center allowed me to be successful in my evaluation efforts. Eventually, my work will be integrated into a bigger scientific analysis that will explore the histopathological differences between SCTLD and other tissue-loss diseases, particularly White Band Disease.

Veterinarians Can Help Corals, Too

As veterinarians, we are called to aid a plethora of species and conserve the ecosystems they belong to, especially when they are afflicted with disease. Simply put, veterinarians have a wide array of tools that can be used to enhance the incredible work that biologists and other conservationists do. This includes standardizing the terminology used to describe disease patterns, applying biosecurity principles to aquariums that house corals as part of restoration efforts, and, very importantly, safeguarding the use of antimicrobials.

Other ways in which veterinarians can impact the coral ecology field include the development of criteria for health certificates for appropriate transport, creation of treatment modalities, and the application of advanced diagnostics. Without a doubt, veterinarians will continue to be instrumental in our fight to conserve and eventually expand the planet’s critically needed coral reefs.

I was very fortunate to receive funding from both the Cornell Yang Center for Wildlife Health and Dr. Rodman Getchell’s Aquatic Animal Health Program at Cornell University. Without them, I would have never been able to work with the dedicated folks of FUNDEMAR in the Dominican Republic or USGS in Washington. In addition, I owe immense thank yous to Dr. Aldo Croquer, my PI in the Dominican Republic, and Dr. Aine Hawthorn, my PI in Seattle. Their guidance cemented my desire to work with corals in the future, and their wisdom shed light on the complex nature of SCTLD. Finally, thank you to Carla Conway, the amazing histology technician at USGS, and Someira, Michael, Andreína, María, Nairobi and all of the amazing people at FUNDEMAR who taught me that hard work isn’t hard when you love what you’re doing.

Hery Ríos-Guzmán, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine DVM Class of 2024, aspires to be an aquatic veterinarian upon completion of his veterinary degree. Originally from Puerto Rico, he hopes to use his knowledge of aquatic species to aid coral reefs and the animals and humans that depend on them in the Caribbean and beyond. He aims to accomplish this by working in a public aquarium, providing veterinary support to coral scientists, and/or completing a PhD in coral ecology and disease.

All images provided by Hery Ríos-Guzmán.