Wildlife as a Window to Environmental Pollution in the Galápagos

Puerto Las Tablas, San Cristobal Island, Ecuador –

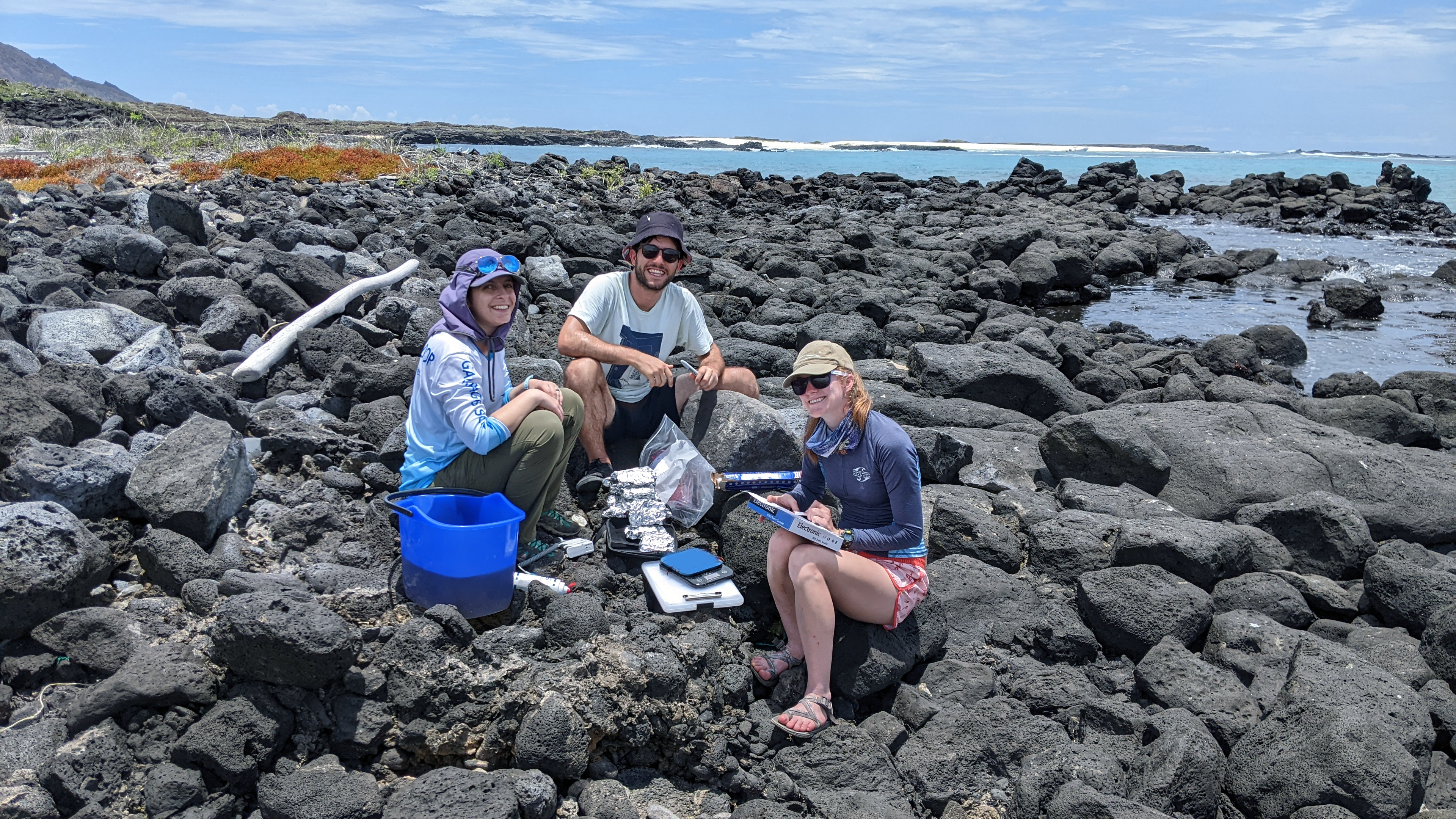

The equatorial sun is fierce and radiates off the field of lava rocks that make up the rugged shoreline. My co-investigators and I are swiftly processing twenty Sally Lightfoot crabs that were collected from the nearby rocks. For each crab we individually identify them, measure dimensions, obtain a body weight, perform a physical exam, and determine a heart rate to assess their health.

While Sally Lightfoot crabs (Grapsus grapsus) are found in places besides the Galápagos archipelago, they are native and almost ubiquitous here. The crabs spend their days moving among the rocks and using both of their claws to pry off and eat algae found in the intertidal zone. Most visitors to the islands catch a glimpse of these bright red, yellow, and blue animals that dot the shoreline, but if you look closely enough you will notice my favorite feature of these crabs: their pastel pink eyes. In my brief time working with these fascinating animals, I noticed that they are always astutely observing their surroundings and have incredible visual acuity that allows them to detect far away threats.

I am part of a multi-national team of researchers who are investigating the impact of plastic pollution in the Galápagos. We want to determine the levels of microplastics, the extremely small remnants resulting from the breakdown of plastic pollution, in animal species in the Galápagos. So far, this collaborative microplastics research effort has studied sea turtles, marine iguanas, salema fish, sea lions, and, now, Sally Lightfoot crabs.

This week’s team is composed of Galápagos National Park rangers, fishermen, marine biologists, PhD candidates, veterinarians, and veterinary students who represent three countries and eight different universities, including University of San Francisco Quito, North Carolina State University, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, University of Barcelona, James Cooke University, and Michigan State University. Dr. Greg Lewbart and Juan Pablo Muñoz Pérez led the week's efforts in collaboration with the Galapagos Science Center.

Today, we traveled two hours by boat to reach Puerto Las Tablas beach on the remote, eastern coast of San Cristobal Island. Despite not seeing another boat nor signs of human activity for the majority of our journey, this beach has plenty of visible plastic debris, such as bottle caps, ropes, pieces of styrofoam, and plastic bag fragments. We call this type of pollution macroplastics because it is visible to the naked eye. A recent study on the island found that this beach had the highest amount of macroplastic of any site on the island, likely because the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt current directly deposits debris on this windward site. The effects of pollution are felt farther and wider than I would have supposed.

To better understand the plastic pollution in this environment, we need to harvest the Sally Lightfoot crabs for microplastics analysis of their gastrointestinal tracts. Our team is evaluating a method to humanely euthanize the crabs while retaining their tissue integrity for accurate sampling. After a health assessment, each crab is placed in an overdose of anesthetic that is dissolved in the water. The crabs quickly fall asleep and are euthanized in about 30 minutes. Because the anesthetic eugenol is a natural oil derived from cloves that does not persist in the environment, there is no concern for environmental contamination. Our hope is that this method is technically accessible for other biologists who want to optimize the welfare of their crab study subjects.

Our team also sampled crabs on two leeward sites of the island–one remote and one near a city. Will the crabs on the visibly polluted Puerto Las Tablas beach have higher levels than crabs found on clean beaches near human development? If so, what does that mean for the health of the humans, the animals, and the environment that inhabit this region? We have only just collected our samples and there are many more hours of data processing and analysis ahead of us, but we are very interested to see what we can learn from these beautiful crabs.

Dr. Emma Houck is a veterinarian who applies medical knowledge to improve the health and welfare of wildlife species in managed and free-ranging environments. As a clinical veterinarian, she provides specialized preventive and emergency care to the animals at the Rosamond Gifford Zoo in Syracuse, NY. She also trains future veterinarians in classroom and clinical settings by connecting their traditional training to the vast biodiversity of the animal kingdom. Emma’s clinically-oriented research optimizes the anesthesia, analgesia, euthanasia, and welfare of wildlife—from megavertebrates to invertebrates.