Diving Into Conservation: My Externship at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center

By Katie Broikos, Cornell DVM ‘26

Introduction to the Georgia Sea Turtle Center

This past summer, I had the opportunity to travel to Jekyll Island, Georgia, where I served as a veterinary student extern at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center (GSTC). As part of the Jekyll Island Authority (JIA), GSTC provides rehabilitation, education, and research programs focused on conserving local wildlife and their habitats. At GSTC, I spent my time in the Rehabilitation Department, which triages, diagnoses, and treats sick and injured sea turtles as well as other native reptiles, raptors, and shorebirds. Working alongside two outstanding veterinarians and veterinary technicians at the center’s hospital, I had an excellent opportunity to learn about coastal wildlife medicine. This unique and versatile experience was made possible by the Cornell K. Lisa Yang Center for Wildlife Health Student Support Fund.

My Experience Practicing Wildlife Medicine in Georgia

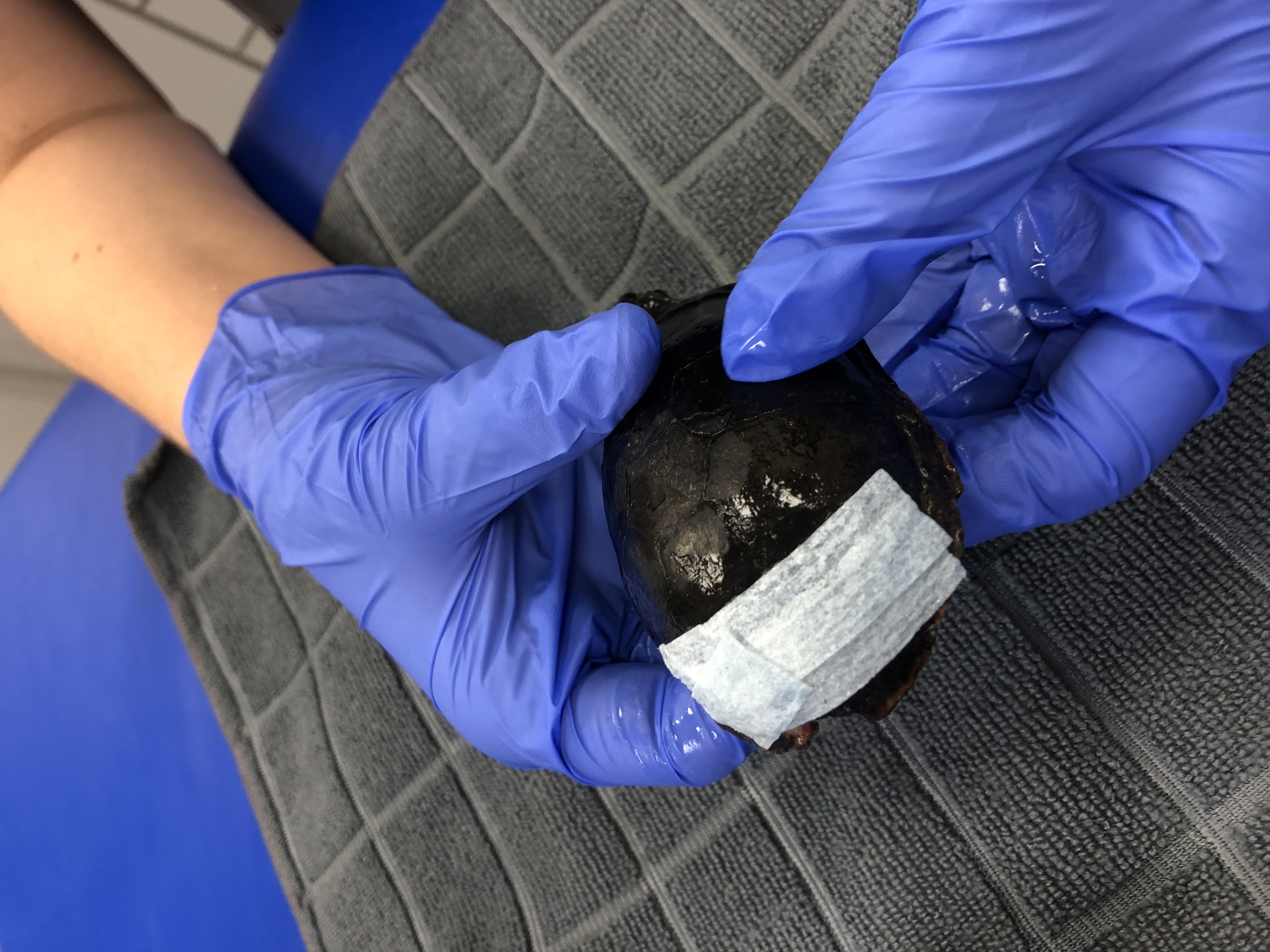

Patients are admitted into the center through various channels, including calls from the public reporting injured wildlife and sightings of injured animals by GSTC’s and JIA’s patrol and research teams. A range of animals were admitted while I was at the center, from eastern box turtles to alligators. One of the most memorable patients during my time there was a severely injured loggerhead sea turtle. Upon arrival, we began photographing and measuring the turtle to complete the Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network (STSSN) Stranding Report. We then collected a blood sample to help enhance our understanding of the animal’s condition and inform the most effective treatment plan. The team used ultrasonography to evaluate the turtle’s heart rate, and we also administered antibiotics, vitamins, and wound care to address potential infections. Lastly, we provided pain medications and fluids. We wanted to obtain radiographs of the loggerhead, but ultimately decided it would be too stressful for the turtle. In the end, each step of the triage and treatment was critical in stabilizing the patient.

Most of my time at GSTC was dedicated to performing daily treatments, which allowed me to refine my patient handling techniques. I became proficient in handling a variety of species, including diamondback terrapins, gopher tortoises, eastern mud turtles, eastern box turtles, Kemp’s ridley sea turtles, and, with assistance, alligators, loggerhead sea turtles, and green sea turtles. When not holding the patients, I performed or assisted with treatments. I frequently administered medications both subcutaneously and intramuscularly, and assisted with gavage (tube) feeding, bandage changes, passive range of motion exercises, and shell repair. The goal of each treatment was to improve the animal’s quality of life and eventually get them back to their home habitat.

Diagnostics played a critical role at the GSTC hospital. We routinely collected blood and performed regular assessments of packed cell volume, total solids, and glucose. Microscopic examinations of blood disease processes and infectious agents. This environment allowed me to practice these skills extensively. I also witnessed and assisted with many imaging modalities from radiography to endoscopy. If patients were stable, we obtained radiographs upon intake, as they provided information on the general shape and position of internal structures. Radiographs were particularly valuable for visualizing eggs in female patients. Ultrasonography provided detailed images of tissues and internal organs, and was primarily used in turtle patients to examine heart rate as well as the size and condition of their bladder. Endoscopy was used to examine the coelom, cloaca, and esophagus for various diagnostics and treatments. For example, the endoscope proved useful during a hook removal procedure in the esophagus of a green sea turtle and for many egg removal procedures and treatments of egg-bound diamondback terrapins.

Additionally, the veterinarians had established connections with a local medical hospital, allowing us to bring turtles in for computed tomography (CT) scans. The CT scans gave us a 3D perspective that helped us understand the extent of injuries in our cases, especially spinal injuries. One of the spinal injury cases involved a gopher tortoise that was admitted with an impacted carapace fracture over its spine. Despite receiving surgery to debride the impacted carapace and decompress the spine, the tortoise exhibited spinal walking and hindlimb paresis. The team then performed myelography with CT. The myelogram showed the contrast moving past the compression and to the brain, revealing that the spinal canal remained intact despite the compression. This finding indicated a more promising prognosis, and we proceeded with further decompression of the tortoise's spine in hopes that more nerve and motor function would be regained.

Another invaluable diagnostic tool we used was necropsy. Postmortem examinations were conducted on every patient that died, providing profound insights into the cause of death and an anatomy lesson. I was fortunate to participate in several necropsies at GSTC, where I learned not only the methods and techniques of dissection but also gained detailed knowledge about the anatomical differences among various species, including alligators, loggerhead sea turtles, diamondback terrapins, great horned owls, red-shouldered hawks, and black scoters.

While at GSTC, I also participated in various surgeries including repair of severe flipper lacerations, fish hook removal, and surgical debridement of a severely fractured carapace. I scrubbed in for the fish hook removal surgery and assisted in closing the incision with a horizontal mattress suture pattern. Additionally, I intubated one of our loggerhead sea turtle patients before the surgical debridement of their carapace. I also frequently assisted with anesthesia during surgeries and manually administered positive pressure ventilation (PPV) with an Ambu bag.

Reflecting on my Externship

I valued the chance to contribute to GSTC’s work both medically and educationally. One of my favorite aspects of the treatments was participating in the behind-the-scenes tours, where guests could enter the treatment room, observe our work, and ask questions. Each tour provided the opportunity to interact directly with the public and make a positive impact. We explained what we did in the hospital, the common reasons animals are admitted to GSTC, and how people can help prevent human-caused injuries and reduce the number of animals admitted. Another rewarding experience was participating in a turtle release in July. GSTC staff successfully returned six turtles to the ocean, and the large supportive crowd made the event even more meaningful.

My externship at GSTC combined my two ideal career fields: aquatic medicine and wildlife medicine. With its innovative and supportive staff, a diverse range of patients, and conservation-focused mission, GSTC was the ideal setting for my externship. I am now invested in following advancements and developments in reptile medicine. My time at GSTC provided valuable hands-on experience with various unique reptile species and treatment methods.

Additionally, I gained an interest in pathology, fascinated by the depth of knowledge that can be learned from necropsies. Ultimately, this experience has furthered my career by expanding my professional network and connecting me with veterinarians and experts in the aquatic wildlife medicine field.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the Cornell K. Lisa Yang Center for Wildlife Health Student Support Fund for their support. Their dedication to advancing wildlife research and conservation made this project possible. I also want to acknowledge the staff at GSTC, especially Dr. Boylan, Dr. Schaffner, Mikayla, and Lydia.

Katie Broikos, Class of 2026, is a third-year veterinary student at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. She received a BS in Biology and Animal Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation in 2022 from the College of Arts and Sciences at Canisius University. Katie is interested in wildlife and aquatic medicine and plans to pursue a career in marine animal rescue.

Photos provided by Katie Broikos.

Please consider giving to the Cornell Yang Center for Wildlife Health Student Support Fund to help provide more hands-on experiential learning opportunities for students passionate about wildlife health and conservation.