Dhole Health and Conservation

Unlocking the secrets of one of Asia’s least known carnivores

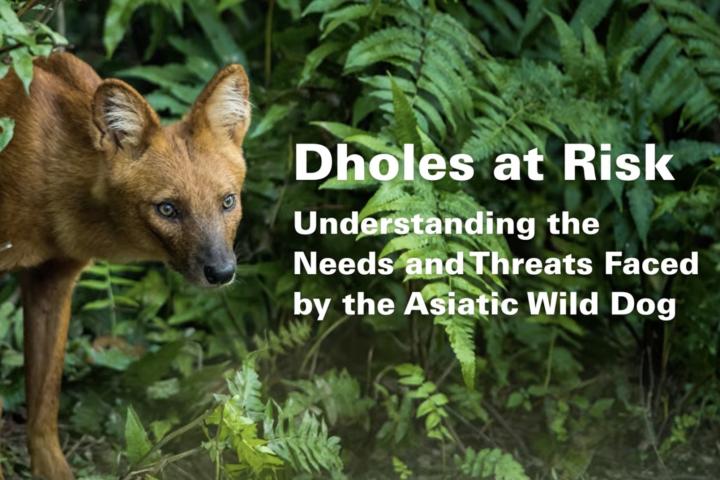

The Asiatic wild dog (Cuon alpinus), or dhole, is a conservation underdog. As a retiring species with an elusive nature, dholes are rarely observed and have received little research attention across most of their distribution. Despite a range contraction that compares with that of the tiger, dholes have garnered only a fraction of the public awareness accorded to their feline cousins, with both now classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

Populations have been lost across most of the species’ northern range, from Central Asia through Russia and the Korean Peninsula, leaving remaining populations scattered in pockets of suitable habitat across South and Southeast Asia as well as parts of China. Dholes are social hunters and work together to chase down large prey such as deer or wild cattle with sufficient meat to sustain a hungry pack. As forest specialists, dholes employ vocalizations to maintain contact with their packmates, utilizing a variety of calls and whistles to ensure social cohesion, which has led to their alternative moniker, the ‘whistling dog.’

Dholes Under Threat

Loss of prey is the main factor driving the decline of dholes across their range. Dholes, unlike more omnivorous canids, possess anatomical features adapted to an almost purely carnivorous diet, which renders them vulnerable to declines in prey populations. Depletion of prey resources by people has driven dholes out of much of their former range, confining most populations to protected areas where hunting is controlled.

Dholes are one of the rarest and least understood of Asia’s carnivores.

Historically, dholes were regarded as vermin by the British Raj, whose bounties drove declines across India to favor wild game species. Similar anti-predator policies in the Himalayan kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan led to the widespread use of poison baits during the 1970s and 80s, which led to dramatic reductions in dhole numbers in both areas. Dholes are now confined to just 11 countries, but these include some of the most populous nations on Earth. Inevitably, dholes and their prey compete with people for space, and habitat conversion and degradation have greatly reduced the areas suitable for their survival.

Health Threats to Dhole Conservation

Dholes are susceptible to many of the pathogens that circulate among domestic dogs, including rabies virus, canine distemper virus (CDV) and sarcoptic mange. These highly transmissible pathogens spread readily among pack-living species and are well-known for impacting the conservation of other threatened canids, such as African wild dogs and Ethiopian wolves.

While anecdotal accounts of rabies and distemper outbreaks in dhole populations have been reported, the significance of these pathogens remains poorly understood for a species that is so challenging to observe and so rarely handled. Nonetheless, abundant free-ranging domestic dogs remain a constant reservoir of these pathogens, and domestic dog CDV outbreaks have coincided with local declines in dhole numbers. Understanding how disease impacts the viability of dhole populations is an important first step to designing effective mitigation strategies.

Dholes in Nepal

Barely larger than the state of New York, Nepal boasts some of the most diverse wildlife habitat in Asia. Historically, dholes were found throughout the country from below 500 feet to over 14,000 feet above sea level, but their numbers declined significantly due to persecution aimed at reducing livestock predation. Today, dholes are best known from adjoining Chitwan and Parsa National Parks in the lowland Terai region, where they face competition from growing numbers of tigers. Yet, isolated reports from around the country suggest that the species persists more widely in remote valleys of the midhills and on the slopes of the high Himalayas.

We are working through the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Dhole Working Group (part of the IUCN Canid Specialist Group) to foster a community of Nepali students and conservationists to work collaboratively and strategically to advance our understanding of dholes and their conservation needs in the country.

Advanced Tools for Dhole Research

Researching cryptic species like dholes can be challenging, as their signs (such as paw prints and scats—also known as feces) are more often observed than the animals themselves. Consequently, we need to develop new and innovative methods to reveal how this elusive animal lives day to day, season to season.

Examples include analyzing scats to detect dhole DNA to confirm their presence and refine maps of their distribution. This presence data can then be utilized to develop occupancy models to understand how dholes are utilizing their habitat, and how their decisions are influenced by the presence of their prey and competitors.

Scats also contain genetic sequences from the pathogens and parasites that infect dholes. In Thailand, we are collaborating with researchers from Kasetsart University and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute to detect these genetic signals in dhole scats, as well as those of the domestic dogs and other wild carnivores that live alongside them. Understanding the risks that pathogens represent for dholes, and the mechanisms through which they are exposed will allow us design methods to prevent infections and keep dhole populations healthy.

The rich vocal repertoire used by dhole packs represents a novel target for monitoring populations in the wild. Cornell University is a global leader in the use of machine learning to study wildlife vocalizations. We are working with the K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology to develop algorithms for use in remote monitoring of dhole calls in the field.