Beagles and Wildlife Conservation

Wildlife populations around the world are facing the ever-increasing threat of extinction. Sometimes we can look to our domestic species for a solution. Using beagles and in vitro fertilization (IVF) techniques, Cornell reproductive scientists have produced the world’s first “test tube puppies.” Why is this important? By using the domestic dog as a model, we can develop assisted reproductive technologies (ART) to save wild canids. Working with our partners at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, this technology is poised for application in endangered species.

Assisting Reproduction

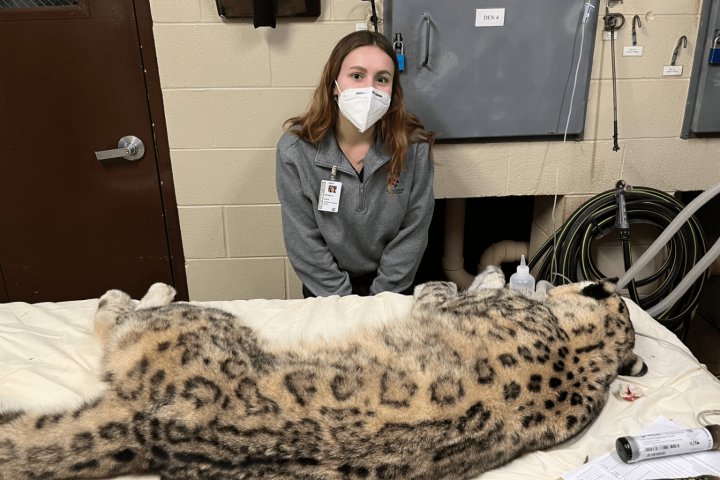

Captive breeding programs involving endangered and threatened wildlife species are increasingly turning to assisted reproductive technologies (ART) to maximize the chances of producing viable offspring. A combination of ART and captive breeding helped save the black-footed ferret from disappearing from this planet forever. Cornell researchers are also collaborating with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute to determine if measurements of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), used as a monitoring tool in human reproductive medicine, can help predict whether a cheetah will produce mature eggs for fertilization if we stimulate her ovaries with hormones. Having such an assay could help increase the candidate pool for assisted reproduction by including older animals who might have otherwise been excluded. AMH evaluation might also prove to be useful in other species for which ART is being considered.

Life after Death: Genetic Rescue

When an endangered male animal dies, is that individual’s ability to contribute to the gene pool over? Maybe not, if you can collect its sperm. What if death occurs before an animal reaches sexual maturity and doesn’t have any sperm to collect? New research utilizing testis tissue xenografting (transplantation) could allow scientists to collect and utilize viable reproductive stem cells from tissues harvested from deceased animals. These technologies could help secure the genetic legacy of an animal long after it’s gone.

Shipping Sperm, not Elephants

Elephant populations are in peril. Captive breeding can provide an important hedge against extinction, until we can resolve serious issues of poaching and habitat loss in the wild. However, even when males (bulls) breed well with the females (cows) in their group, there are critical obstacles to having sustainable captive populations. We are conducting research that can lead to the creation of better semen collection methods to improve fertility, and ensure the long-term survival of the captive population.